I’m driving with my puppy, Sophie, on my lap. I push her off. I’m too close to the car ahead of me. I’m struggling to find the brake, afraid we’re heading for a crash.

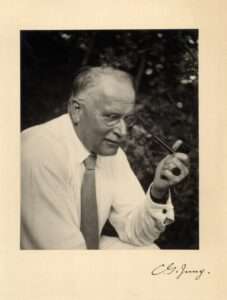

How would Swiss psychologist Carl Jung (1875-1961) interpret this dream? Would he note that “Sophie” comes from the word Sophia, meaning wisdom? Since the famous analyst saw all dream images as representing parts of the dreamer, perhaps he’d identify Sophie with my own “instinctual” self. What part of me is going too fast and liable to “crash?”

Jung often spoke of the “second half of life” (after age 40) as a time of deep personal renewal, often preceded by confusion and angst. How did he know what I was going through? At least I was imploding on schedule.

In the space of a year, I had lost three different career paths. I’d been pursuing each part-time, simultaneously, and now couldn’t do any of them. Actually, I had relinquished one voluntarily–a 25-year pursuit of theatrical success. Mistress Theatre had finally taken her toll on me–in time and money. The other two part-time vocations were abducted in a staggering succession of uncanny and strange events outside my control. Because of changes in a law, and in boardroom rules, I could no longer legally work in these positions. The rapid, immutable rulings left me dismayed, disoriented, but also feeling directed. I was “supposed” to be doing something else. But what?

Just before this career free-fall, I had plunged into a voracious reading frenzy of Jungian psychology. I couldn’t explain why. I just needed to read the books.

Jung’s writings were too difficult for me, so I was reading works by his protégé, Marie Louise Von Franz. She was the ideal mother– offering encouragement and inspiration to my battered psyche. I devoured her stories of myths and dreams. They were good, wholesome food, nurturing long epic dreams of my own. My experiment: to read everything written by the prolific Von Franz, to record my dreams every night, and see what would happen.

I started my reading on Christmas break. I brought home 10 books. They were rarer items–retrieved from academic libraries throughout Illinois. I carried them like freshly picked produce. They were my prize and my solace. Life had become confusing. I didn’t know where my career was going and these books were a temporary release. I plodded through them, even though I only understood half of what I read. After two weeks, I went back for another stack.

While I kept a steady diet of Von Franz, I also read other prominent Jungians, referenced in other books or on Amazon. My reading list kept growing—edited in a file on my hard drive.

A year later, I’m talking shop with Jungian Stephen Martz.

Martz seems to be a kind and gentle man – someone who could entice you to bare your soul. His analyst’s grey hair speaks authority. His intense gaze suggests intelligence and enthusiasm. If Jungian therapy were in my budget, I’d ask Martz to be my analyst. He exudes warmth and wisdom–and lives in my neighborhood.

It’s a treat to interview Martz for a magazine article on Jung and dreams. It’s a subject close to my heart.

“What have I learned?” Martz responds rhetorically. “To take the unconscious seriously. Life is so much more than what I see and touch and smell. It’s a journey inward, to a different reality.”

Jungians typically interpret everything in their life, not only dreams but daily events. As Martz sits in front of a poster depicting a traveler at a fork in the road, he tells me about a recent flood in the basement room where we’re meeting. From my reading I know that water can signify the unconscious. A flood could represent being lost in one’s unconscious dreams, fantasies or personalities.

I don’t suggest this but ask if he has an interpretation.

“Not yet,” he said. “I’m just sitting with it and seeing where it goes over time. But it was duly noted.”

I tell him, “It can drive me crazy, trying to interpret every single thing that happens.”

“Well, there is Freud’s famous quote, ‘there are no accidents,’ and I think that is mostly accurate. But Freud also said, ‘sometimes a cigar is just a cigar,’ and I think that’s true for Jungians as well. I will know in time what the event meant.”

I appreciate his patience and am glad I didn’t offer my simplistic interpretation. “You don’t feel any pressure to understand it right away?”

He doesn’t. Martz takes a long view of his dreams and the journey of self discovery. He believes that, “when you’re working analytically, the longer the period of time, the better you understand (dreams or events). It may take many a circle before we really get it.”

I keep circling around this topic. My editor asks me “why?” “Why do I feel compelled to read Jung?” I’m embarrassed that I can’t seem to answer her simple question. I’ve been struggling with this assignment, to write about my Jungian experiment. Am I simply reluctant to reveal myself? Or is it because I’m actually unaware of what I’m doing? Will my editor think it’s a cop-out to say, “I don’t know?” For me, my lack of awareness is further proof of Jung’s theories. He said that all of us are mostly unaware of our motivations. He said that we receive most of our perceptions and intuitions from outside our normal waking consciousness.

I ask Martz to describe a “formative” dream, one that was decisive in his life. He finds it difficult to choose one. As he opens a simple spiral notebook with great care and tenderness, he decides to quote a recent dream.

“I meet a man who is younger than I. He is carrying a newborn infant. We talk and I recall when my children were infants. He gives me the baby to hold. I am deeply moved by this very tiny baby in my hands.”

He closes the notebook. “I will probably be working with this dream for several months. I think it has a lot to say about my ‘charge’ as I go forward as an analyst–particularly on my ability to hold the tiny and the vulnerable.”

I too recorded my dreams in a notebook but then bought a small digital recorder since I could never decipher my scribbled notes. Now I whisper my dreams (to not wake my husband), and then diligently type them in the morning. Sometimes an interpretation seems obvious– A man stuffs paper towels in my mouth, trying to stop my singing. (How often has an inner saboteur stopped me?) But many times I’m frustrated. Why is my unconscious so obtuse? Elegant people are having a party in a very dilapidated home. What does that mean?

I ask Martz why interpreting dreams is so difficult.

“I think it’s like learning a foreign language, only harder. It’s the language of symbols. We’re not taught that language. We’re so rational and so scientifically oriented; we don’t believe these images. We don’t trust them. I have one client, when he tells me a dream he challenges me, ‘See if you can get something out of this!’”

He laughs at the memory. “I think it takes years and years and years and sometimes the hardest to decipher are our own.”

I’ve been recording my dreams for over a year. At the beginning, I had four or five every day. Now they’re tapering off. Even though I couldn’t interpret them, I hoped that the act of recording would bring me a benefit. Von Franz counseled me: if I’d humbly open myself up to the reality of my unconscious, I’d be rewarded.

So I recorded my dreams as an act of faith. A friendly greeting to my unconscious. Almost immediately, I felt subtle but powerful shifts. My hunches grew stronger and I had a strong premonition (just before the career earthquake), of a different professional path to explore. It was a very palpable feeling of direction. Synchronicities (the term Jung gave to coincidental events that have meaning) keep happening. These “coincidences” propel me on this new path that I sensed over a year ago.

I also began to have “aha” moments, suddenly seeing my quirks. Jung says that our conscious self, our ego, is like a man walking in sunshine–unaware of the shadow that follows his every move. I was starting to see darker parts of my personality, the shadow that others saw but I had not. I caught fleeting glimpses of embarrassing traits—such as my impatience with children.

I ask Martz, “How does the public misunderstand dreams?”

“They think, ‘I dreamed of something just as a rehash of the day.’ They don’t sense that they are important. The problem in our culture is that everything is ego.”

Maybe that’s why I cannot easily answer the question, “Why am I compelled to study Jung?” My “ego,” my conscious self doesn’t know. Why am I driven to cover my home with alchemical art? I don’t know. Not fully. I only know that buying this strange art, reading these indecipherable books and recording my dreams feels right. “Feels right:” there is some part of me that knows why, and this part is pleased.

When I talk about this double of myself, I remember that Jung spoke of this also–in his autobiography. I am only now, nearly two years into this experiment, beginning to have a sense of what he might have meant. My double, call it my unconscious half, perceives the world much more completely. She picks up a million nuances that don’t quite register in my waking mind. She retains memory of all the events that I’ve repressed or forgotten. And she knows all the parts of me, not just the parts I approve of, but all parts–those sinister and virtuous.

It feels impossible to explain and piece together all the separate strands that form a path and then a life. While struggling with this assignment I’ve been examining the twists and turns of my life’s journey. I realize that my Jungian experiment was a search for guideposts on the path. And also a search for God.

When I interviewed Martz, I was intrigued with the poster in his meeting room. I now see why. The poster spoke of my current situation–a traveler at a fork in the road under a sign that points in two directions. One says, “There’s no going back there.” The other points a way ahead.

I’m starting a new path with dreams helping to guide me. Describing their content may not make much sense to you (or to me), but even without understanding them they are providing the tiny intuitions I need.

Mordred (a hawk in a recent dream), lands on my shoulders. I’m waiting for the pain of his talons sinking into my skin, but there is no pain, only our flight together. It is a good dream, one that encourages me as I pursue a new path.